Ten Predictions for the 2020s

Ten predictions for the next ten years.

#1: Enterprise software in the 2020s will replay Softbank’s Capital-as-a-Moat disaster of the late 2010s.

Here’s a thesis I’ve been chewing on for a little while: The 2020s might become a real slog of a Red Queen’s Race that could mess up the model for funding and selling enterprise software. There are two problematic trends here; each of which on their own would be fine but the combination is dangerous.

The first is increasing vertical specialization. The previous/current generation of enterprise software is pretty good for a broad swath of things, so in order to be meaningfully better, the next generation of SaaS businesses will probably have no choice but to go industry vertical-specific. Expect a lot of “Linkedin for X, Bank for X, ERP System for X” type pitches for a while, where the core value proposition is “Software that’s actually built for your industry as opposed to being one-size-fits-all.

The second trend is AI as the next big technological wave for business services. Martin Casado of a16z and Gavin Baker had good tweetstorms on how AI will change the business model and funding implications for enterprise software the other day. The issue is that AI is really expensive. It’s more compute intensive, more data-intensive, more resource-intensive in general. The rewards will be immense, but AI businesses will face heavy fixed and variable costs. So there’ll be a huge advantage to being the market leader; more so than in the previous generation of SaaS businesses.

These “structurally lower enterprise software margins as the world moves to AI”, as Gavin put it, take us towards a more winner-take-all dynamic in enterprise software VC. The scale advantages in AI businesses may simply become a new frontier for capital-as-a-moat funding strategies, and there’s a real danger that enterprise software could turn into Softbank 2019 v2.0. That’s life if you’re going horizontal, but it’s dangerous if you’re going vertical.

Stuffing more and more capital into industry-specific, vertical businesses, i.e. the foie-gras funding model, could be a disaster. It’ll force early stage VCs to demand more deal structure, as they preemptively defend against mega-rounds down the road. It’ll force products to de-specialize, in order to preemptively accommodate the massive TAM that their funding requires. And it’s all but a guarantee that the winner in each vertical will be some overcapitalized monster. This stinks, honestly. In a Red Queen’s Race, no one wins.

#2: There will be no major form-factor that supersedes the smartphone. The phone is it.

If you went forward in time to 2029, you’d be surprised that the phones are more or less the same. The 2×5 inch glowing glass rectangle will remain more or less similar as our common interface with the internet and with the world. Nicer in some ways, and they’ll have some genuinely cool AR features, but other than that? We figured out the phone. It’s gonna stay put now.

What’s inside the phone will be radically different, for sure – the “re-nationalization” of technology into Western and Eastern tech stacks will place some really interesting pressures on the hardware under the hood. It’ll be especially interesting to see what happens to the Android ecosystem as these pressures intensify.

But the average user won’t notice much of a physical or UX difference between today’s physical iPhone X and 2029’s iPhone XXII LX Turbo Limited or whatever it’s called. I think AirPods will be an incredible accessory for Apple over the next decade, and they’ll sell a ton of em, but I don’t really buy the “they’re the new computing platform” story. Same with the watch. I’m pretty bearish on headsets, glasses, or anything that obscures or layers over your vision any time soon.

The place where phones will evolve the most in the 2020s will continue to be the camera. Apple will probably acquire some fancy DSLR manufacturer and have a big event about it. Meanwhile, machine vision will continue to improve, and the scope of things we’ll able to do with it will accelerate at an astounding rate. There’ll be some creative use of the non-visual spectrum that unlock some cool features. In not too long, there will be an iPhone app called “find my keys” where you can wave the phone around the room and it’ll lead you to your keys even if they’re buried under the couch.

Under the hood, I expect that well over half of the computing horsepower in a smartphone will be dedicated to vision within a few years. AR will arrive in a hundred different little ways, including some unexpected monster hits in the vein of Pokemon Go. But you know what’ll be surprisingly the same in 10 years? The standard way we’ll interact with these games and with our world will be familiar: through our phone screens, almost identically to today.

#3: A tale of two cities: the looming feud between the SF and NYC tech scenes

I hinted at this a couple months ago in The Founding Murder and the Final Boss, and the response was pretty telling: a bunch of SF people saying “What? There’s no rivalry. That’s silly.” While the NYC people, as if through gritted teeth, more or less responded “mmmmm”.

For a long time, the Bay Area has been peerless as a destination for building, funding and scaling startups. Nowhere else compares. Nowhere else has the talent network. Nowhere else has the critical density of young angels and the social status subsidy it creates. Nowhere else has the ease, fluidity, and excessive credibility in the system that you need in order to build first and ask questions later. But that won’t be true forever.

The New York City tech scene has gone through its ups and downs, but it’s finally starting to accumulate a critical mass of success. Real Deal exits like Datadog, Flatiron, Jet and Peloton are starting to occur regularly. The angel scene is strong, and the product community is great. Most importantly, NYC is such an incredible place to live – especially compared to San Francisco – and has so many other advantages as a financial and media capital that in the long run its advantages for acquiring and accommodating tech talent at scale are undeniable.

Up until this point, the relationship between the NYC and SF tech scenes has been friendly and productive. But that dynamic is changing: SF and NYC Tech used to be a fundamentally unequal relationship, and that kept it cordial. There was no rivalry because they weren’t peers. But now little brother is all grown up. As the relationship turns into a peer relationship, admiration is turning into resentment: slowly, for now, but inevitably.

The inflection point, of course, was this:

The WeWork saga did a lot of damage to the NYC – SF Tech relationship. WeWork in its rise was a genuine startup miracle. Adam Neumann took every lesson to be learned on reflexivity, every conjuring trick that the Bay Area had figured out, and put on a master class with it. On the way up, SF made it one of their own: look at this great thing we, the tech community, built.

And then what happens when it all fell apart? The Bay Area talking heads fall into lockstep, immediately, to deny that WeWork was a tech company, that it was symptomatic of anything systemic, or that it had anything to do with the reflexive conjuring formula that they had invented. San Francisco collectively scoffed, sorry to this man. This man is from New York. We don’t know him.

In the next decade, watch for this rivalry to take shape. San Francisco’s pole position as the leader of the tech world will remain intact. But as the city increasingly turns into a developing country, with a gated class of tech power guarded by protection rackets and surrounded by an increasingly failed state, their loss will be NYC’s gain.

Each city’s tech scene will come to resent the other’s more and more, and allegiances will be hard to shake: NYC will resent SF for its endless reservoir of technological and tech-cultural capital; SF will resent NYC for being a place people actually want to live. But most importantly, both tech scenes will come to resent each other for being more alike than different with each passing year.

Watch this story. It’s going to be really fun to spectate.

#4: At some point in the 2020s, the following headline will get printed: “Crypto Finds its Killer App: Guns”

Crypto is a dumpster fire right now. Narrative after narrative has fallen apart under external attack, or been memed to death through internal sabotage. The worst may be yet to come, if the Tether story lives up to even half of its potential.

But Bitcoin is holding up. The price may not be, for the time being, but the core network is proving to be annoyingly resilient. The awful years are a much better test of crypto’s real potential than the good years are. It’s not going to go away, even if the current crypto scene largely does.

The crypto scene we’ve come to know over the last few years has been a bit all over the place, but the theme in common to most of it has been “new finance” / “stack sats, get rich”. Over the next ten years, after our current hangover gets truly washed out, a new one is going to emerge that’s a lot stronger, a lot darker, and a lot more true to the original vision than many people would like to admit: crypto as a part of “Dissident Tech”.

Expect the crypto community to retrench and double down on a core value proposition: crypto as a tool for political and societal dissenters. This means people who don’t really care what the price of Bitcoin is; they actually care about it being uncensorable. That means people who are doing illegal things, it means people on the wrong side of governments, or it could simply mean freedom-oriented people. But the narrative will turn really sharply once the core value proposition embraced genuinely becomes “be un-censorable”, as opposed to “get rich”.

Expect to see Bitcoin, and cryptocurrency generally, start to show up in a lot of thematically adjacent products, businesses and brands. Guns are going to be one of them. As more countries crack down on gun ownership, and as flashpoints like Hong Kong become internet-fluent conflicts, guns and crypto will get a lot closer together, as will efforts to crack down on both.

#5: Higher ed: undergrad will stay the same, but grad school will get blown up

Two parts to this prediction: the first I don’t want to go too much into, but I think that the narrative that American higher education is going to collapse in a matter of years is just totally false. There are so many structural forces holding the system in place, and (for most middle or higher income families) so much professional and reputational risk associated with not going to college, that the undergraduate experience isn’t going anywhere. I’m happy that we’re having a conversation around alternatives, but don’t count on any dramatic change any time soon.

Grad school, on the other hand, is a totally different story. I’m going to write a whole newsletter about this in the new year but for the time being, I think both “classes” of grad school – professional degrees and research degrees – are going to be disrupted pretty dramatically, and pretty soon.

Unlike a typical undergraduate education, the value of a professional graduate degree can be squarely articulated in terms of career mobility. Many of these degrees are where ISAs will really shine as a business model. But who will run them? Perhaps organizations cut in the same vein as Lambda school, but more likely it’ll be employers themselves.

It’s already standard practice in some white collar businesses for your employer to pay for you to go get an MBA. Expect a lot more of it this coming decade, as tuition sticker prices continue to soar, and larger employers can more effectively “negotiate” on behalf of students, like a health insurer would. It’s only a matter of time before these large employers say enough is enough, we can do this ourselves, and do a better job at it, too.

There’s a really great business to be started here – be the white label platform that lets large employers become professional educators, both for their own cohorts of junior people and also anyone else who makes admissions grade. Professional graduate degrees feel like a good target here because their output ought to be both the most measurable and the highest leverage.

Research graduate degrees, on the other hand, are under less of a direct threat but are arguably in bigger trouble. PhD students pursuing academic research are feeling a more desperate squeeze every year, as they’re smushed through a funnel that keeps them in an overworked, underpaid apprenticeship for the most productive years of their lives. But there’s no way around: the point of a PhD is to establish yourself as a brand in your field, and the only way for a young scientist to do that is through their supervisor’s lab, and through their university department. The grad school model is incredibly leveraged on this constraint.

But you know what’s blown the whole thing open? Twitter. Twitter is genuinely revolutionizing graduate research, in a way that’s eye-opening for graduate students and quite threatening to their supervisors. Twitter gives students a path to establishing their own brands, both for the work they’re doing but also for their critical thought, their participation in the scientific community, and their individual strengths and personalities.

This is really exciting for grad students who know how to use Twitter and the rest of the internet as a tool to build their academic careers. But it’s really dangerous for the model, which is leveraged on the fact that students do not have access to such tools, and can only acquire a brand and access through their supervisors. I’ll write more about this in the new year, but the consequences could be bizarre, and pretty significant for the way that scientific research gets done.

#6: There will be a major speculative bubble in biotech companies.

We’re going to have another bubble. This one will be less like Crypto 2017 and more like Dot Com 1999: it’ll be in the public markets, with retail mom and pop investors, and covered conventionally (and enthusiastically) in the media. And it’s gonna be in biotech.

It’ll have the three ingredients you need for a genuine bubble:

First: “I’ve seen the future and it’s incredible, we have to get in now even though we don’t understand it.” Biotech is really an ideal sector for mass speculation. It impacts everybody, and it’s inside everyone and everything: the TAM of “biology” is infinite. It’s incredibly complex, so it’s easy for novices to grasp onto a story and its importance without understanding the reality of it. And it’s full of high-leverage potential: it’s totally plausible that biological breakthroughs in health, manufacturing, fuel, etc could generate tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars of value.

Second: A critical mass of retail investors who are hooked on high returns, as the current bull run eventually runs out of gas (although that may not be for several years!). We’ll have the conditions where a large enough number of regular people, especially Gen Xers who did well in the past 10 years and who are moving into retirement, now have slush money to invest (and the time and boredom to get hooked on it).

Third: A new kind of financial innovation that becomes the instrument of speculation. These aren’t a necessary component of bubbles, but they sure help. In this case, I bet there’s going to be some new clever financial product that bundles and securitizes the highly speculative IP of biotech companies, in a way that legally lets retail investors buy them through an ETF or something. You can imagine the rationale: “Imagine if regular people could’ve owned a basket of the fastest growing tech unicorns last decade; well, this is that, but for all of these high-potential biology breakthroughs. Make sure you don’t miss out on $BIOVX!”

The bubble may not be in therapeutics; or at least if it is, it won’t be around single-cure narratives like “We may have a pill for Alzheimer’s”. It’s going to be more like, “We’ve made a general breakthrough in biology that has changed the game for everything.” I think the best contender is some breakthrough around energy conversion and biochemical production, where there’s a plausible thesis for “everything that used to be off limits is now economically plausible.”

So that’s how you’ll have companies promising these crazy business plans and future visions, like in the early days of the internet, that were based on something genuinely real, but by no means were ready for prime time. So you’ll see speculation on all sorts of production – synthetic food, fuel, chemicals, building materials, who knows what – that runs completely out of the real of common sense, but has that critical amount of FOMO and imagination to set off a real bubble.

#7: The only tech giant I’d be seriously worried about is Google.

Apple and Microsoft will be fine. Amazon continues to be a cash flow monster, and has been able to put their cash to work more impressively than any other business on earth. Despite what you see on Twitter, Amazon remains overwhelmingly popular and loved by both Democrat and Republican voters, and well over half of American households are Prime members: any kind of government intervention or antitrust pursuit would prompt a consumer revolt like we’ve never seen before. And even if they tried, Amazon could break themselves up first, and be back at work by Monday.

Facebook is going through a phase of enormous scrutiny, and I really do understand where bearish sentiment around that business comes from. But all the while, Instagram became the most important social media platform in America, and more importantly, WhatsApp has cemented its dominance in much of the rest of the world. Facebook’s ads business remains elite, and they’re getting serious about Marketplace and other forms of commerce. (Who knows what’ll happen with Libra, but mock it at your peril.) At the end of the day, Facebook is what the people want, and if you dig into it, they’re what the government wants too.

That leaves us with Google. In one sense, Google has the strongest position of the five. They won the internet. Like, they really won- not just their dominant position in search advertising and consumer services, but the fact that anyone who wants to build a new piece of the internet has to ask Google’s permission first, or else find out that what they built won’t fit. As I wrote a few months ago in Google Chrome, the perfect antitrust villain, they’ve mastered the art of Strategic Openness.

I’ll admit: the inner chambers of Google are largely a mystery to me. But I’ve heard enough conversations in private, from people who know, that Google could be in serious antitrust trouble – or maybe even more serious trouble, with other branches of government. They engage in by far the most actually anticompetitive behaviour of any tech giant. Their size, moat, and voting structure makes them effectively immune to shareholder activism of any kind. They have the most problematic relationship with foreign powers out of any tech giant. Their employees are either protesting or bored. Google has the most at stake to lose.

Act One of Google was building the world’s greatest search engine, with the world’s greatest business model. Act Two of Google was colonizing the infrastructure of the internet, like a technological British Empire, in order to protect and fuel its crown jewel capital. The 2020s will be Act Three. As the decade begins, Google may well face the biggest real opponent they’ve ever fought – the United States – at a moment where its internal morale and purpose are crumbling and adrift. They print money, but if you ask me, they’re at risk.

#8: There will be a significant moral panic around microplastics – not due to their environmental effects, but for their health effects.

At some point in the 2020s we’re going to have another Leaded Gasoline crisis. We’re going to learn that some sort of chemical or microscopic thing that’s inside everything, all around us, actually has some horrible health effect we never knew about before. My pick for what it’ll be? Microplastics – particularly the microplastics inside clothing, like athleisure.

The funny thing is, we already know that all of the fancy microplastic stitching and fabric material we put inside athleisure are terrible for the environment. That stretchy, comfy feeling comes at at an affordable price point, but a terrible environmental one – we already know this. But no one cares. We’ll start caring, though, when it turns out that they’re hazardous to us in some way we never understood before.

I have no idea what kind of health hazard it’ll pose, but it’ll be one that takes a long time to develop, and where childhood exposure gets linked in a study to some awful condition that happens to you later. It could be that all these cheap, fast-fashion clothes are secretly off-gassing some volatile organic compound that we breathe in and gives us cancer later, or maybe it could be something like physical micro plastic particles getting on our hands, and then into our stomach when we eat, and then it gets linked to some digestive disorder or intolerance, or maybe it kills our gut bacteria, or I dunno.

But by the time we find out, we’ll have been wearing these clothes for 10+ years, and it’ll be a major crisis. In the end, it may well be less of an actual public health risk than we thought, and (hopefully) a lot less than leaded paint and gasoline. It could be something entirely different, but I bet you there’ll be some major crisis around our collective, silent poisoning by something that creates a real panic some time in the next ten years.

#9: The 2024 and 2028 elections will be overwhelmed by “Campaign Hacking”: not by foreign governments or enemies, but by opportunistic hustlers and entrepreneurs.

American elections are unique in that go on for so long (more than a year! That is just absolutely incomprehensible to people in other countries) that they create a special kind of media environment. There cannot be a single story arc, or even a reasonable number of story arcs, that fills such a huge void for content.

If you want attention, there’s an opportunity here. If you can conjure up a campaign story, the media sort of has to cover you in a way that’s not otherwise the case. They need election stories, and they can’t miss out on something that becomes one. Back when the news media was a more organized and gated industry, there was a certain degree of “seriousness” you had to hit in order to meet this requirement. But today’s that’s obviously no longer the case: engagement on its own, anywhere, is all you really need to kick the cycle off.

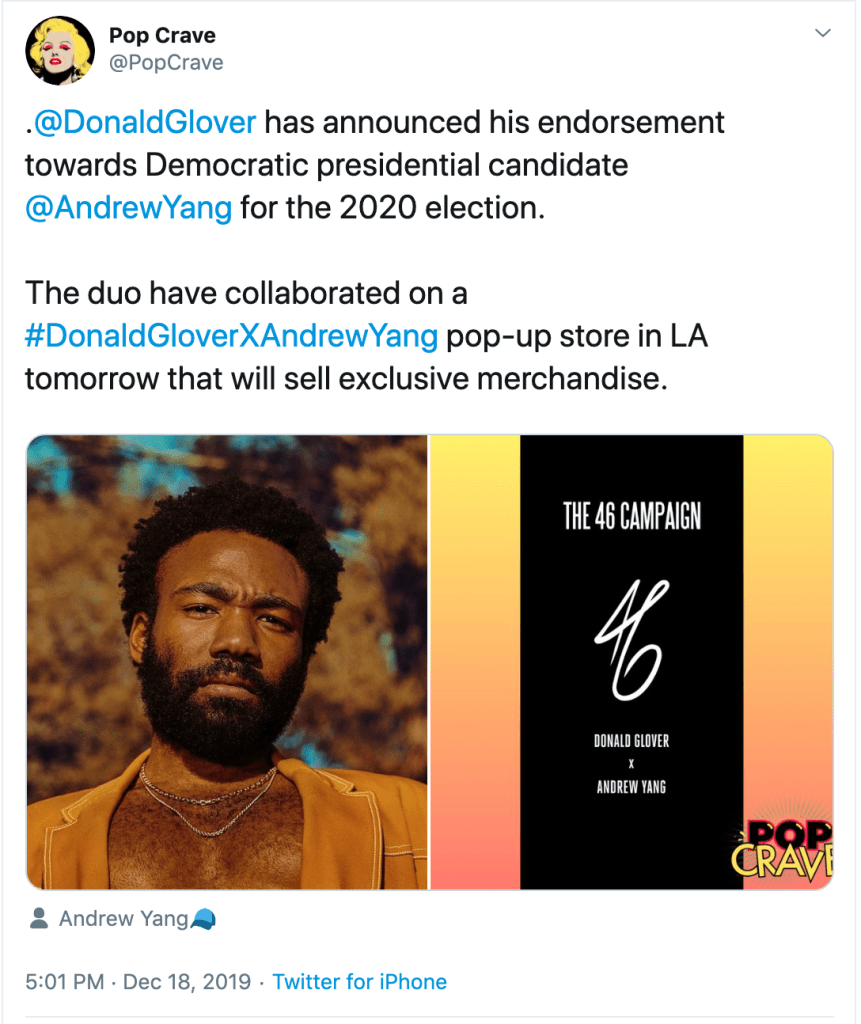

I got to thinking of this the other day when news dropped that Donald Glover was endorsing Andrew Yang for president through … an LA pop-up store collaboration? Like, what is this exactly? It feels like a hack of some kind. It’s clever, for one thing; it got everybody talking about it. And when you think about it, why shouldn’t you leverage a presidential endorsement to sell merch and extend your own brand? What else could you do?

To a point, this is fine. Think of it as the “DJ Khaled Campaign Technique”: if you figure out how to boost politicians and yourself by standing next to them and toasting another one in a way that’s actually useful, well, great. But when we start to think of it as a hack, all of the variants on it you can try, it’s gonna get wild.

One hack might go something like:

1) Make a big splash of some kind, either with or without a presidential candidate’s support, in a way that associates you with the candidate and makes it “campaign newsworthy.”

2) Congratulations, you’re now a character in the campaign story. Use it! Go say something controversial: “Post Malone, who dropped a new streaming track in support of the John Delaney campaign last week, has now come out in favour of legalized dogfighting.” (Instagram Story: 2 million likes.)

3) Look at that, you just permanently saddled the campaign with this association, and have a permanent invitation to reopen discourse whenever you want: next streaming track, add a bunch of lines about dogs and then bait the campaign to respond. (Next day’s Washington Post A2: “Delaney Campaign dogged by controversial endorsement”. Streaming track: chart topping.)

4) Repeat as often as you like. The fact that you’re a campaign story now makes you automatically newsworthy. If you do it right, the storyline can be compelling and entertaining enough that it can temporarily overwhelm any of the actual serious campaign stories going on.

The old days when there were only a few serious news networks that had serious editorial judgement are gone: they have to compete with whatever’s going viral now. Meanwhile, there’s a new rising class of viral celebrity that doesn’t have traditional brands, managers, or handlers to keep them in line from saying controversial statements. Their power comes for their audience alone, so they can say whatever they want, in a way that wasn’t true for celebrities before.

We really haven’t yet seen the real extent of what the internet will do to political campaigning. I’m betting that the next creative wave isn’t going to come from the campaigners, but instead from opportunistic hustlers on the outside who figure out how to hijack them.

Campaign media has always been, you know, the media – there’s a certain slipperiness and grift associated with capturing and holding ratings. But I think it’s likely, given the direction that things are going, that the next couple elections are going to descend further into explicit engagement hacking. At the root of it, really, is a reflexivity hack: the hard and fast rule “if it’s a campaign story, then it’s automatically news” is just designed to be abused. Hustlers and entrepreneurs, even more than politicians themselves, will figure out the formulas for how to force the media to cover you as a campaign story, almost certainly to the detriment of the primary process itself.

#10: A real startup scam is going to seriously spook the Silicon Valley community.

I’ll leave you with an oddly specific prediction, about one of my perennially favourite topics.

The prediction is this: some time in the next few years, there’s going to be a hot deal going around the VC Associate group chats and the angel backchannels. It could be a consumer company with monster engagement numbers in another country. Or maybe it’ll be a deep tech venture, founded by a couple of genius technical founders. Either way, it’ll be a deal you just have to get into.

The founders will be people in the community that everybody know. They’ll be thoughtful and responsive, pedigreed and respected in the scene, and will manage their fundraising tour like pros. They will open up the round to a few junior investors and angels, only to inform them the next day, we’re so sorry – we’re oversubscribed, and there isn’t room for you anymore. Devastating. But then! At the last minute: “We found room for you. Are you able to wire us the money tonight? If you can, we’ll let you in on this, but we’ve gotta close now.”

A few days later, we find out. The founders have absconded without a trace, with the funds that were wired in early. The engagement numbers were gamed: they looked real, but on further inspection were built out of mobile engagement farming. Or perhaps that technical expertise and potential was real; it’s just vanished, off with the founders. Whatever happens, there’ll be no doubt about it: this was a scam.

My prediction is that a high profile fundraising scam will happen in Silicon Valley. I’m not talking about a Theranos-style scam (“They said the blood tests worked even though they didn’t”) or a WeWork-style “scam” (“They painted a rosier vision and financial picture than reflected reality). I mean like a real scam: like founders raise a super hyped round of funding, then disappear with the money. And the repercussions from that scam will leave a surprisingly big chill that lingers for a while.

Now why will this matter so much? In terms of absolute dollars, a few million disappearing isn’t all that serious a threat. The real damage and the real threat here isn’t financial, it’s social and reputational.

I’ve long believed that the real mystery of Silicon Valley isn’t the outsider question, “How is Silicon Valley so wild and crazy”, but actually the insider question: “How is Silicon Valley so stable?” It’s built on speculative finance, it’s full of experiments whose outcome you can’t know for years, and it has to move fast enough and fluidly enough that (at early stage anyway) it effectively works on the honour system despite the FOMO environment. It’s so interesting how, in this environment, there aren’t any scams like this.

I’ve long believed that, yes, Silicon Valley is a bubble – but it’s a bubble that has evolved a strong social contract. That social contract is critical to the whole place working, and not flying apart at 100 miles an hour into scams and grifts, like crypto has (that’s what a real bubble looks like). Silicon Valley has socially engineered something special – the upside of a bubble, without the ugly side.

Silicon Valley works because it has a code of conduct. Freud would say it’s evolved a superego: a collective social pressure enforcing a certain set of norms about how you behave – when it’s okay to get away with something, and when it isn’t. There are rules.

It’ll be interesting to see what happens when this superego gets challenged. One of the important components of Silicon Valley working well is early stage investors willing to write checks without really having to worry about the downside – the worst you can lose is 1x your money. Financially, that’ll be true, scam or not. But reputationally? If a high profile scam becomes the talk of the town, there’s nothing scarier than everyone else knowing that you fell for it.

The older, seasoned VCs won’t be directly bothered by this at all. They won’t fall for it in the first place, and they’ll be experienced enough to stay the course. But for a large crowd of younger investors, both junior partners at funds and especially the horde of younger angel investors who provide that critical early funding lift to the tech community, it’ll be really spooky. They’re going to experience a new kind of hesitation, and feel a new kind of friction to pulling the trigger on a deal, that can be lethal for seed investing.

If a critical mass of early investors in Silicon Valley all of a sudden get way more nervous about writing checks, you could see a real snap freeze in seed deals. One high profile scam won’t break it, but it’ll shake the innocence away a little bit.

Like this post? Get it in your inbox every week with Two Truths and a Take, my weekly newsletter enjoyed by thousands.

Recent Comments