The Audio Revolution

If I told you about a piece of consumer electronics technology that:

- A billion+ people own and use every day

- Has changed those people and their world in some pretty radical and consequential ways

- Gets more important every year, but not much attention – and the little attention we give it is mostly a sideshow that misses the real story in plain sight:

I’d be talking about these.

Headphones, and the audio they hiss into our ears, changed everything. Our social values and instincts have changed because of headphones. Populism and politics have changed because of headphones. I think there’s even a case to be made that Donald Trump is president because of headphones. The audio revolution happened while everyone looked elsewhere.

The Basics of Information

To really understand the impact of audio, we need to go back to basics and understand how audio works as a medium, independent of its content. What does audio have to say? What does it do to us, in plain sight, that’s gone unnoticed? We need to go deep into some Marshall McLuhan territory, and appreciate what he meant by his famous line The Medium Is the Message.

McLuhan is one of two 20th century figures – the other is Claude Shannon – to truly grasp how and why information technology works. Claude Shannon laid the groundwork for McLuhan by discovering Information Theory, and defining information in a counterintuitive but powerful way: as resolution of uncertainty.

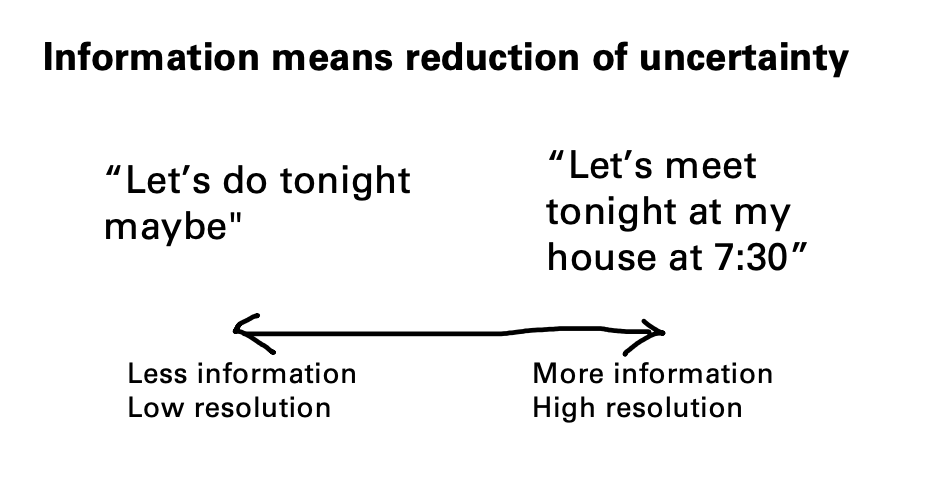

Compare these two sentences: “Let’s meet tonight at my house at 7:30” versus “Let’s do tonight, maybe.” Which one contains more information? The first one. It resolves uncertainty to a higher degree, which is why we say it’s “higher resolution”.

If you’re told “Let’s meet tonight at my house at 7:30”, you’ve received a pretty complete, high-resolution dose of information. On the other hand, “Let’s do tonight maybe” is lower-resolution, with some gaps you’ll need to go fill yourself. It could mean yes, it could mean no. Eventually you’ll figure it out, but it requires active work on your part to interpret your friend’s communication style and understand the message correctly.

We live in a world of information, and we often think of information in terms of sensory input coming at us. But that’s not really information. Information isn’t what we’re told; it’s what we understand.

Hot and Cool Media

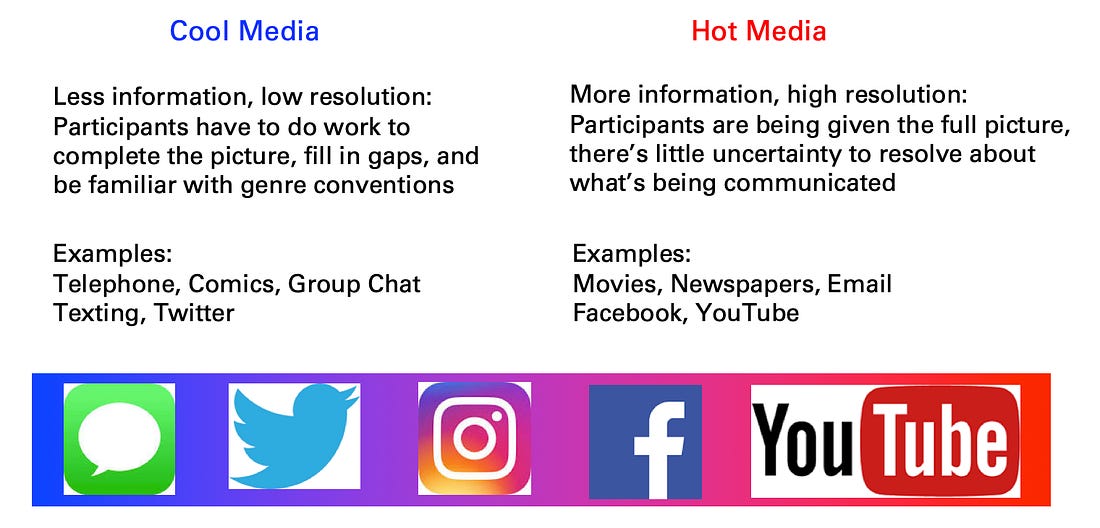

Now let’s add McLuhan to the picture. McLuhan’s first insight here is that different forms of media create different kinds of spaces and stages for information and understanding, regardless of whatever the content might be. You can arrange them on a spectrum, from high-resolution to low-resolution. McLuhan labeled this spectrum “Hot” to “Cool”.

Some forms of media and communication inherently transmit information in high definition, where what’s being communicated is right in your face. Uncertainty is resolved immediately and thoroughly. The media yells at you, like a newspaper or an action movie: it doesn’t hold back. There’s no guesswork or participation required on your part. McLuhan calls this “Hot” media.

Other forms of media and communication transmit information in lower definition. The participants have to do work to integrate several different pieces or senses, including gaps in information that must be filled in or genre conventions that must be followed, in order to complete the picture. A typical telephone conversation is lower resolution media, because a large part of the message being communicated is obscured or unsaid: it isn’t in the words, but in the gaps we must fill in. This is “Cool” media.

The concept of Hot and Cool media took me a long time to really understand. But when it suddenly clicked, it clicked all at once. I think some people have a hard time figuring it out because McLuhan’s illustrative examples in Understanding Media are from another era. “The Waltz is a Hot dance, because it’s unambiguous mechanical mashing, whereas the Twist is a Cool dance, because you have to integrate information and fill in gaps in real time” was a great example then, but less so now. People also get thrown off by his description of TV as a “cool, tactile medium”. Remember, back then, TV was a glowing fuzz of white dots and muffled audio you had to piece together – a totally different medium than film (hot back then, and now) or TV today (which has heated up a lot since McLuhan’s day).

So here’s an explanation in terms of media we know today: texting, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube.

Texting: ice cold. The entire point of texting, particularly for young people, is that it’s a way to communicate that reveals very little information. Uncertainty and ambiguity is the point. Texting, especially a group chat, is often like a game of “what’s said versus unsaid”, where gaps must be filled in. It demands active participation on your part to complete the picture of what’s being communicated. (The dreaded “…” in iMessage, which says so little but draws us in, is Cool Media.)

Twitter: cool. Twitter is tricky because there are many different ways to use it. Breaking News Twitter, for instance, is fairly hot. But Twitter the social network, the way I use it, is quite cool. It’s a low-resolution, character-limited format where the majority of what’s being communicated is actually just offscreen, out of the picture. The greatest tweets and the funniest jokes on Twitter are incomplete information: they’re pure punchline. The setup goes unsaid; you have to already know it, or go figure it out. It takes a lot of work to use Twitter successfully and you have to fluently understand its genre conventions in order for it to make sense. Twitter, when used optimally, is Cool Media.

Instagram: warm. The main content being communicated is all visual, and you don’t need to understand genre conventions as much. Instagram in its early photo filter days was fairly hot media, as is classic photography, but it cooled down when it became the de facto social status app. Now there’s interplay between what’s posted and how many likes it gets, and from whom, and other social dynamics like private versus public posting. There is still some ambiguity, but as a medium it’s more information-complete than Twitter or texting.

Facebook: hot. Unlike Twitter, which is a muttering mass of inside jokes, or Instagram, which is warmer but still has some cool elements to it, Facebook is more like a newspaper. It’s not holding anything back. It’s a patchwork mosaic of yelling: Acknowledge this! Be angry at this! Celebrate this! There’s not a lot of mystery on Facebook, and it doesn’t take much fluency to use it correctly. The information being communicated is all right there, blasted at you. Facebook may have started out cooler, back when it was college kids navigating social status (as Instagram is used now). But it’s heated up steadily since then.

YouTube: scorching hot. We’re going to talk about YouTube later.

Now, remember: when we say Hot and Cold media, we’re not talking about the content. We’re talking about the medium itself. The Medium Is the Message means is that the choice of media creates a stage for what follows. Hot media creates space for hot communication; cool media creates space for cool communication. Hot media heats things up; cool media cools things down.

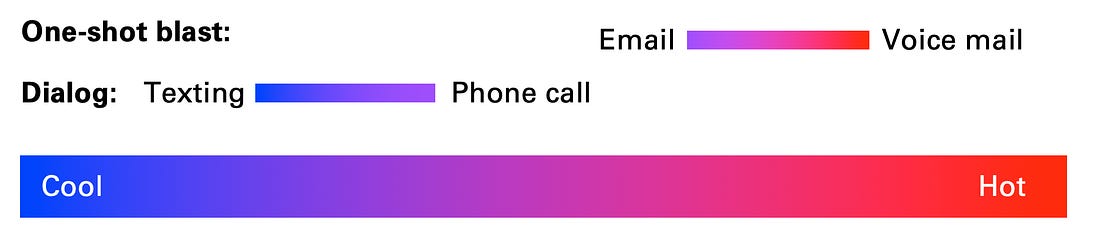

Think about the difference between communicating by texting (cool) versus email (hot). Typographically, there’s no difference between the two. But email is understood to be a single-shot method of communication, which is hot and high-resolution, whereas texting is understood to be a dialogue: it’s a cool, chatty medium by nature, where little information is actually exchanged. Communicating by email, regardless of the content, will generally heat things up and force directness. Communicating by text will generally cool things down and invite ambiguity.

Meanwhile, the physical properties of the medium you choose will also influence the temperature of what’s being communicated. A photograph is hotter than a pencil: they both make pictures, but one makes low-resolution sketches and the other high-definition images.

What’s hottest? You might think that the highest-resolution format of all could be visual, typographic or video. But it’s not. It’s audio.

Audio: the hottest format of all

Audio, especially verbal speech, is tremendously high in information content. Most people are unaware of this. We mistakenly think of information as sensory input being thrown at us, usually with a bias towards our visual senses. But information isn’t what we’re told; it’s what we understand. Audio and speech resolve uncertainty and communicate meaning more powerfully than any other format.

Audible speech burns hot with information. Intonation, accents, innuendo, vocal phrasing, emphasis, pauses, all communicate far more than a transcript can. Audio is the format for “You all know exactly what I’m talking about, because of the way I’m saying it.” Audio is how you communicate what you really mean, straight into ears, headphones and car radios, intimately and directly. Music is good at this, but speech is even better.

Here’s an exercise you can do: speaking out loud, say the word “tonight” twenty different ways, where each way is communicating something distinct. You can say “tonight” in a way that’s intrigued, satisfied, tired, horny, dejected, anxious, suspicious, hesitant, desperate, or any number of ways – and the person you’re talking to will know exactly what you mean. You can’t do that easily with image or text. A transcript of the word tonight just says tonight: flat, ambiguous. Our eyes treat it neutrally. But our ears don’t. Our ears are hyper-discriminatory.

Whatever it is that’s being communicated, audio will heat it up. Imagine you’re in a confrontation with your landlord, and you can communicate either over text messaging or by phone (cooler, back-and-forth dialog) or by email or voice mail (hot, one-shot blasts). Text keeps things chill, whereas audio forces the issue.

When you present information in an audio-first format, or especially in an audio-only format, it heats up what’s being communicated, and saturates its information content. What may have seemed ambiguous or flat when presented in text or mixed media format won’t be interpreted ambiguously by your ears. Your ears understand what’s really being said, and they seek hot content.

There’s a famous story about the Nixon-Kennedy debates that I misunderstood for a long time. Following a presidential debate between Richard Nixon and JFK, those who had listened over the radio overwhelmingly felt that Nixon had won, whereas those who watched on TV felt that JFK won. I remember originally hearing this story and thinking that the point was somehow that TV was more “superficial” than radio, and that JFK’s handsome face or easy on-screen charm somehow overruled the debate’s substance on TV but not on the radio.

I’ve now come to understand that this wasn’t the point at all. The lesson has nothing to do with the content of what either of them were saying. The content doesn’t matter. What matters is that Nixon was a Hot candidate: sharp, saturated with information, abrasive, and in your face. But JFK was a Cool candidate: relaxed, speaking easy, in slogans that invited multiple interpretations, creating plenty of gaps for the audience to fill in themselves.

Hot, high-resolution media like radio created space for a hot style and messenger like Nixon really well. But cool, low-resolution media like 1960s TV rejected him. Nixon sounded powerful and alive on the radio, but abrasive and mismatched on TV. Meanwhile, Kennedy seemed slow, empty and lethargic on a hot medium like radio, but fit smoothly and confidently on TV. It couldn’t matter less what they said: our cool and neutral eyes liked Kennedy; our hot and discriminatory ears liked Nixon.

Hot media seeks and creates hot content and hot messengers. A voice like Howard Stern, coming straight into our hyper-discriminating ears, is a powerful thing and when we hear it, we want more of it. Put headphones on, turn off the lights, and put Howard’s voice in your ears – audio only, in the dark – and you’ll experience heat. Cool messages and messengers won’t cut it anymore – not on hot media; not on headphones. They feel flat and dead.

On other forms of media, cool messengers and cool messages and cool values and cool society do well, because there’s a cool environment for them that fits right. Barack Obama was a successful Cool candidate. Yes We Can was a perfectly cool message: it doesn’t really say anything, but helpfully leaves a gap for us to fill in however we’d like. That message fit perfectly on the cool format of mid-2000s mixed internet media, with Yes We Can as a cool, blank canvas. It’s an entirely different temperature from Make America Great Again. There’s no ambiguity there. We know exactly what Make America Great Again means. If you’re not sure, go listen to it spoken out loud, on talk radio.

A good match between message and medium goes a long way; a bad match usually fizzles out fast. That’s why The Medium Is the Message – dominant cool media mean popular cool messages, which in the long run – averaged out over all their content – just means a cool temperature. Hot media mean hot messages, hot temperature, and hot consequences. It’s relatively rare for mismatches to thrive.

There’s a possible exception here worth noting, which is Donald Trump’s Twitter account. It’s quite ironic, actually, that people think of Trump – a supernaturally hot entity who rides a hot political wave and a hot tide of resentment – as somehow this great master of Twitter, one of the coldest forms of mass media today.

Here’s the thing: he’s not actually a good fit for Twitter. His tweets are a jarring spectacle, clashing badly with the way the medium normally works. Trump’s tweets only really work because he’s already president, and because the clash is part of the show. And even then, Twitter is not how Trump actually talks to his base or flexes populist power. He did not rise to the presidency because of Twitter.

You want to know where he sounds positively presidential? On the radio.

Trump sounds incredible on the radio.

Information and the Brain

When we say that hot media create space for hot messages, or create a kind of stage on which they succeed, what do we mean by that? Where is that stage? Well, we are the stage. Our attention and comprehension is where information “happens”.

So in order to understand what headphones and audio are doing to us, we need to take a closer look at us: that is to say, our brains.

Brains face an engineering challenge: how to deal with sensory input streaming in, in real time. It’s a speed problem. Individual neurons in your brain can each take somewhere in the tens or sometimes hundreds of milliseconds to integrate and transmit signals between each other. Even basic neural circuits can comprise dozens of neurons. Without some way to speed this up, complex sensory integration or motor output would be impossibly laggy.

We use something called feed-forward processing in order to speed things up. Feed-forward processing is useful when you’re interpreting inbound information that’s familiar or predictable. If you’re reading the sentence: Somebody once told me the world is gonna roll me, I ain’t the sherpest tool in the shed; she was looking kind of ocean (Wait, what?)

What happened? You began the sentence, and then your brain picked up on a pattern it recognized: Smash Mouth lyrics. Then your reading sped up – you already know those lyrics, so you fed them forward into your sensory processing stream. You start skimming: reading in low resolution and filling in the gaps. But then, you hit the word ocean and slammed to a stop: it didn’t fit the model you fed forward. Better go back to reading one word at a time.

Once we start following the known All Star sequence, each additional word contributes almost zero new information, because they resolve no uncertainty. (Filling in The World is Gonna ____ ____ with Roll Me happens automatically). But the word Ocean was new information. You sense, “There’s uncertainty to resolve here”, and flip back into high-resolution information processing, which is much more discriminatory.

Feed-forward prediction is one of our brain’s critical information processing tools. We rely on it continuously, at every abstraction level, from basic raw input up to executive function – particularly for our eyes. Our default way of processing the world isn’t taking it all in finely discriminatory hi-fi, it’s continually assembling and filling in our understanding of the world with what we expect is there.

In real sensory perception, you’re continually making subconscious, probabilistic judgement calls about when to switch into intense, high-res inspection versus when to keep scanning and gap-filling in low resolution. If you look back at those lyrics, you’ll see that I actually wrote “Sherpest” instead of Sharpest, but you may not have picked up on it. It’s a small error, so it may not have flipped the switch. Or maybe it did! With neuroscience, everything is just a probability.

Hot and Cool Brain Muscles

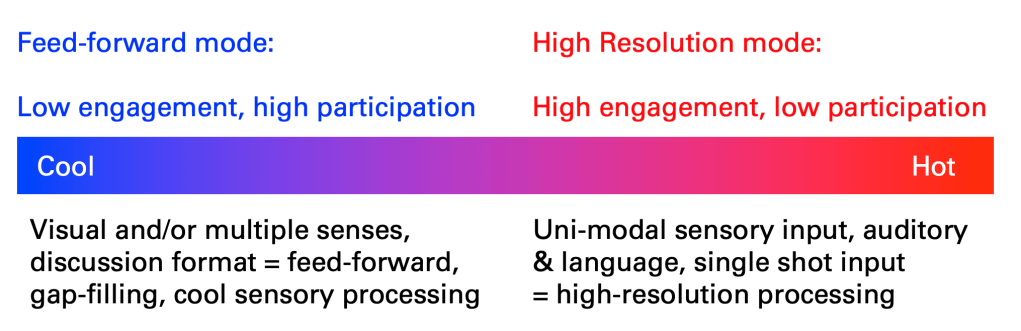

The reason we’ve gone through this little neuroscience lesson is to build towards an important point. The brain continuously triages inbound sensory input into our low-resolution, fed-forward, gap-filling stream and into our high-resolution, information-saturated stream. This should ring some bells: sure sounds like Cool and Hot. And it is.

One of the major differences between hot and cool media that we only briefly touched on before is McLuhan’s classification of hot media saturating one single sense, whereas cool media often integrates multiple senses, filling in a picture from many inputs. How come?

The neurological explanation is illuminating. Sensory input is processed in two different ways: uni-modally (vision only; audio only) and multi-modally (integrating multiple senses together into a complete picture). We don’t totally understand why, but we believe that our uni-modal sensory processing pathways are more sensitive to uncertainty and “New Information” than our multi-modal pathways are. Our neural circuitry dedicated to integrating multi-modal sensory information is less willing to throw the switch into high-resolution, finely discriminating information processing. It prefers to scan in low-resolution and fill gaps. It’s cooler.

Meanwhile, not all senses are created equal. Inbound audio, particularly human speech, is particularly sensitive at triggering the “There’s information to resolve here” mode of sensory processing. Written text, which passes through our language areas (evolutionary speaking, an audio domain) is pretty sensitive too. There’s also a difference between discussion versus monolog formats: cool dialog, where information is communicated in gaps and pauses, asks for more participation (feed-forward gap-filling) than a single-shot, high resolution stream of inbound information.

Now we’re ready to understand the impact of Hot and Cool at ground-truth level:

Cool sensory perception and cool media are low in engagement but high in participation. We are operating in gap-filling mode: doing relatively little engagement with the media (we’re only pulling in a low-resolution sample) but a lot of participation with the media (we’re actively filling in the gaps ourselves, and operating in feed-forward mode).

Hot sensory perception and hot media are high in engagement but low in participation. We’ve switched out of feed-forward scanning mode: doing a lot of engagement with the media (we’re intensely processing a high-resolution inbound sensory stream) but not much participation (because there are no gaps to fill in).

If you remember one thing from this essay, remember this: hot sensory processing and cool sensory processing are like muscles. The more you use them, the stronger they get, and the stronger they get, the more we use them. We used to think that our neural circuits were relatively fixed by adulthood, but we now know better: they’re highly adaptive, and they strengthen and synchronize with repeated use.

As you use cool neural circuits, you create a cool stage that will easily and fluently accommodate cool media and cool messages. As you use hot neural circuits, you create a hot stage that intensely and eagerly accommodates hot media and hot messages. The stage is you.

So how about those headphones?

Old and New Radio

Radio is a perfectly hot form of media. It maxes out all three dimensions we care about: it saturates one single sense, it’s spoken audio that’s high in information density, and it’s a uni-directional blast of information. Everything about the radio medium pushes our brains towards high-resolution, high engagement, low participation mode.

American radio has an interesting history. The earliest days of amateur ham radio gave way to Radio as Big Business, led by the Radio Corporation of America in the first half of the 20th century. (Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch is a good intro in context with other media.) But as television took over much of centralized broadcasting, radio reorganized itself into a vibrant local kaleidoscope of programming: music, weather and traffic reports and especially talk radio.

From liberal pockets on the coast, it’s easy to miss how popular and influential talk radio is in America. The average American adult reportedly listens to an hour and a half of radio a day (!), of which a heavily skewed 15% or so is talk radio. It’s more politically varied than you think, especially if we include internet radio and podcasts, but AM radio has been the power base of the American Right for a long time. It’s an intimate, private format: the host is speaking directly to you, in high definition. The most important place where radio is listened to isn’t in public or even at home, it’s in your car: a private environment where you and Sean Hannity battle traffic together.

Headphones recreate that environment: a completely private space, just for the two of you. Mobile phones and the internet put anybody in the world in your pocket, and then headphones complete the gap. Remarkably, the rise of streaming audio (music, podcasts, audio books, internet radio) has only slightly dented radio listening statistics in America: almost all of this new streaming is additive to the audio we were already listening to.

Next time you’re out, look around at how many people are inside their headphones. All of that audio, all day long, is layered on top of a world of escalating loudness. All of this audio stimulation is doing something to us. Even benign background music has an impact. It’s repeatedly juicing our Hot sensory processing brain circuits, shifting that probabilistic balance a tiny bit, away from cooler, participatory, convention-following, feed-forward processing and towards something closer to an alarm state.

Any individual hour of audio has a negligible effect. But hundreds of them? They add up. That’s why cool media environments make us receptive to cool messages, and hot media environment makes us receptive to hotter messages. With the internet, we find it. The most important modern audio institution is the new elephant in the room, and it’s giving us what we want. It isn’t internet radio, nor is it podcasts. Most people don’t even realize that they’re an audio company.

It’s YouTube.

The scale of YouTube is ridiculous. YouTube reports 1.9 billion monthly logged users, with over a billion hours of content consumed daily. The majority is on mobile. It is the world’s second largest search engine and second most visited website, after Google. 400 hours of content are uploaded to YouTube every minute. Nothing else is this big, except Facebook.

One of the biggest misconceptions of YouTube is thinking of it strictly as a video or visual product. Yes, it’s a video player; and yes, it’s true that there are some specific verticals within YouTube, like gaming or beauty, that are image-heavy. But YouTube’s real heritage and impact aren’t visual. YouTube is amateur radio, at mega scale.

YouTube built an frictionless platform for people to broadcast and communicate with one another. But it didn’t necessarily make content creation easier. It still takes effort, expertise and likely a budget to create content that visually communicates meaningful information. But it’s trivially easy to create content that communicates audibly. Just hit record, point the camera towards you, and start talking. Most of the signal coming out of YouTube is people talking.

I really wonder what percentage of YouTube is consumed audio-only, or at least audio-first (the visuals are playing, but the viewer isn’t really paying attention to them). I bet you it’s way higher than people think. The ability to keep YouTube playing while switching apps on mobile is a major selling point for their premium service; that’s explicit YouTube-as-radio use. We know that Music on YouTube is huge, but it’s not what I’m talking about. I mean: what percentage of all YouTube content, and of all streaming time, is content that’s mainly someone talking, saturating one single sense – your ears – and not much else important is really going on?

If 10% of YouTube consumption falls into this category (and I’ll bet you it’s higher!) that’s 100 million hours of New Radio consumed every day. And this is not lukewarm stuff like Instagram or even loud, indignant rants or conspiracy hoaxes shared on Facebook. This is radio: the format for communicating what you really mean.

As I write this, at a table in the library, someone just in front of me has a YouTube tab open in the background, streaming Ben Shapiro. Courteously for the rest of us, he’s wearing headphones. Their conversation isn’t for us. It’s private.

Headphones and America

People accuse Facebook and Twitter of being misinformation platforms that sway elections, but I don’t really buy it. I think they’re mostly lagging indicators for how people already feel. The kind of urgency that really changes minds isn’t a feeling we learn with our eyes. We learn by hearing it: in intonation, in phrasing, in private, in our car radios and headphones. (Our language use betrays this: we use the word “See” to mean “To check out”, whereas we use the word “Listen” synonymously with “to pay close attention.”) The more we use our ears, the more quickly we’re going to pick up on that urgency. The medium IS the message.

When every American put headphones on their ears and then connected those headphones to the internet, should we be surprised that our national politics, values, and discourse are shifting away from cooler, open values and towards hotter, closed ones? I don’t just mean the MAGA movement, by the way. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are also hot candidates with hot messages, and it’s their moment. (Warren is the first candidate I can remember who uses lengthy, block text writing – also a hot medium – as a legitimate political communication tool.)

There’s a particular kind of message that hot media consumption primes really well, and especially resonates over audio, that has come to dominate the political conversation in America. The message is discrimination. I mean that not just in the way we usually use the word discrimination (as in, exclusionary prejudice) but in a broader sense. In our lifetimes, modern liberalism has built up a cool, open society whose overarching aspirational value is equivalence: the idea of the “level playing field”, both economically and socially. It’s given us equal rights and anti-discrimination laws, on the one hand, and free trade on the other.

The current backlash against liberalism, which is especially well-articulated in the MAGA crowd (where Trump is a perfect orator), is a backlash against this enshrinement of equivalence and supposedly level playing fields – both economically and socially. Make America Great Again really means Let America Discriminate Again. “You’re telling me we’re supposed to believe there’s no difference between X and Y? You and I both know there is clearly a difference.” You can fill in X and Y with “Citizens versus non-citizens.” Or, if you prefer, with “Regular people and rich people.”

This message lands harder over audio than it does in text, video or any other format. On the left or on the right, it doesn’t matter: the specific message varies, but the mechanism is the same. Headphones create a private space for that finely discriminatory message, and a channel through which it resonates the loudest. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that audio has become the most powerful new format for political action on both the left and right in America today: on the left, podcasts; on the right, YouTube.

In Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan spends time ruminating on what happens when hot and cool media enter societies for the first time, or in new ways. The printing press, which quickly spread hot, printed text through Europe, was a pretty big factor in the subsequent centuries of continuous war that followed. More recently, radio has done the same.

Interestingly, McLuhan speculates that England and America were spared from the traumatic effects of hot radio (in contrast to Weimar Germany) because we’d already been “vaccinated” by our higher literacy rates and prevalence of print media. I’m quite sure that the biggest consequences of the Audio Revolution won’t be in the United States. They’ll be in the developing world. I can’t speculate at all on what they’ll be, as that’s truly beyond me, but a world without headphones almost certainly turns out differently.

Less Audio

A few months ago, I stopped listening to podcasts. This was a pretty big change for me: I listened to several hours of podcasts a week, often while commuting or at home, and especially while running. My subscriptions were mostly lighter stuff like comedy podcasts (What a Time to be Alive, Blocked Party, and UYD are my three best recommendations) and generally stayed away from more loaded stuff like politics, sports, or anything work-related. It’s not like I was flooding my brain with radical messages or important information on a regular basis.

But ever since I’ve stopped, I’ve noticed something change about my own writing and thinking. My brain is quieter. It’s clearer, and easier to navigate; like the gain on an amplifier had been cranked up for a long time, and we forgot about it, and only when you turn it down do you realize, “Hey that was a lot”. I think my weekly writing has gotten better in that period of time, and I’ve had a few readers email me and ask if I’ve been doing anything differently. That might be it.

I miss them, but I don’t think I’m going to go back. Only after taking them off do you realize that headphones aren’t all that good for you. There’s a lot of discussion about screen time and how scrolling feeds and glowing screens are having bad effects on us, but a lot less discussion about constant audio stimulation, aside from hearing loss. Maybe this isn’t true for everybody; I know a lot of people swear they’re more focused and productive with music, for instance, and that’s fine. Maybe a hot, hi-fi sensory state is good for some kinds of productivity. Maybe it’s just what people like; no more complicated than that.

But I suggest you give it a try. Go for a week with no headphones and no car radio. See how it feels. It’s an easier experiment to try than going real cold turkey and putting your phone away for an entire day. See what happens when you turn down the gain on your brain’s high-discrimination, hot processing mode. You may not notice anything. But I did.

Like this post? Get it in your inbox every week with Two Truths and a Take, my weekly newsletter enjoyed by thousands.