Positional Scarcity and the Virus

So, everything’s gonna be totally different for, I dunno, let’s say a year. And then at some point, the crisis will be over and life will return to a normal cadence. Then what?

For many aspects of our everyday life, things may well go back to more or less the way they were; perhaps with some modified details (Masks? More emphasis on touch-free interaction?) and different economics (differently organized supply chains with more resilience) but still the same basic setup. However, there are a handful of industries and institutions that seem poised to come out of this crisis looking radically different than when they went in. Two that I hear a lot of chatter about are Business Travel and Higher Ed.

Business Travel and College Campuses have both been essentially frozen to zero, and won’t come come back for some time. In the meantime, we have no choice but to figure out alternative ways to get those jobs done, like online video. The longer this crisis goes on, and I suspect it’ll be a while, the better our temporary solutions will get. I hope so, anyway.

This presents a question: once this is all done, will we go back? In normal times, the status quo here is very expensive: we pay a huge premium for business travel versus a phone call, or for university tuition versus learning online. You can’t help but wonder: if we’re forced for an entire year to forego the in-person benefits of these practices, what happens when life returns to normal?

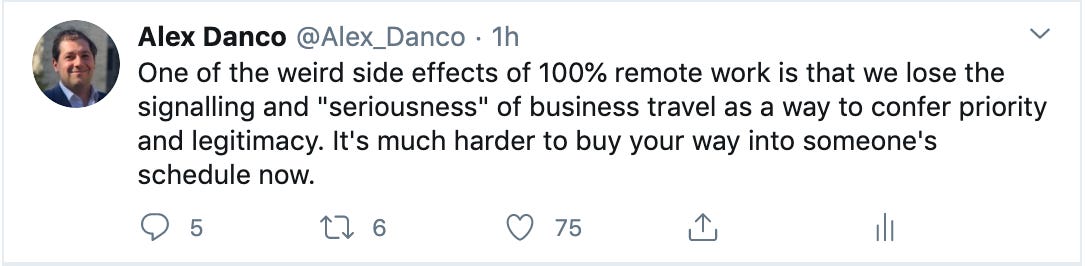

There’s a case to make here, which I see being spitballed around on the Internet a lot, that the old way of doing things is over. Our year of remote-only will dispel the familiar rituals and expose our expensive addictions to these things. And after this is over, we’ll have a harder time with casually approving $4000 of flights, hotels, and lost time for an in-person meeting when a Zoom call could do, or spending $50,000 on tuition for learning that could happen online.

I doubt it. I believe the contra case is actually stronger. Our year of disruption may very well reinforce, not disrupt, the core reasons for why we do these things.

Last year I wrote a post about positional scarcity: in environments of abundance, relative position emerges as a new kind of scarcity that’s expensive and valuable:

Positional scarcity comes in a lot of different flavours. There’s curation: an abundance of people creating music creates demand for record labels, DJs, and other tastemakers to do the job of picking, “Out of all these options, which song should get heard?” There’s prestige: an abundance of prosperity makes it harder to preserve and distinguish high status: “Now that everyone has a car, how do I make sure that my car is the most impressive, and everyone knows it?” There’s access: an abundance of people all vying for each others’ attention and patronage creates a high premium for moving to the front of that line: “How much would you pay to skip the congestion and get to where you need to go?”

Higher education and business travel both fall somewhere in the top right hand corner of the Venn diagram I’d made: they’re both especially good examples of the “Legitimacy”, “Prestige”, and “Proximity” needs that positional scarcity helps to confer.

First, let’s take business travel. Getting on the plane means you’re serious about something. Everybody’s busy; the fact that I’m choosing your one hour in person rather than an entire day of otherwise productive work is a signal: “I’m taking this seriously.” It establishes a concept of “place in line”, with this meeting being at the top.

That kind of commitment is often necessary for everyone involved to prioritize this meeting, and its action items, high enough on their to-do list that things actually get done. You have to take the time and expense to physically situate yourself there, in close enough proximity. Positional scarcity is a zero-sum game, and it’s something we can purchase with our money and effort. The more costly it was to get yourself there, arguably the better. If you don’t take the time to fly over, by the way, you risk being bumped down the priority list in favour of the people who do.

Higher education works in a similar way, although at higher stakes and over a longer time scale. Everyone understands that the university system today works as a credentialing service, where universities must run faster and faster against one another in a Red Queen’s Race in order to preserve the relative rank and elite signalling that they confer on their graduates. A university degree confers a certain place in line for your career, and universities care a lot about making that place as competitive as possible.

Even more importantly, you build a network with other people – both professionally and personally – that does not work without that physical proximity that places you at the front of the line for meeting them. Paying up to attend a brand name school may seem expensive, but that’s the price for securing your place in line, and your proximity to those networks. It may be a totally inflated price, but we pay it anyway.

So now we have this weird experiment for a year where everything has to happen virtually. The pandemic has imposed this new temporary condition where we are no longer able to pay for positional scarcity and access in the same way, because we’re all stuck at home in Zoom meetings. It’s harder to buy your way into someone’s schedule now. And so long as colleges campuses remain closed, it’s harder for prospective college students to effectively buy their way into networks of friends, contacts and career prospects. (I’m sure they don’t think about it that way, but they’re still bummed out.)

Now, there are two competing theories about what’ll happen when the virus recedes.

Theory one says: “All of that spending on positional scarcity; all the time and cost and energy we’re exerting while running the Red Queen’s Race just to keep up and maintain our place in line; all of that is ultimately zero-sum and pointless. The virus is giving us a one year suspension of the race. During that year, we’ll adapt, and ultimately we’ll forget what we were missing. Everyone will stop paying this stupid tax, and we’ll all be better off.”

Theory two says, “If you think that when all of this is done we’re not jumping right back into the race, I have a bridge to sell you. The one-year viral reprieve is going to make it especially clear what were paying for all that time. Also, it doesn’t matter if you disagree with this; as long as at least some of your competitors feel otherwise, you’ll be forced to go along anyway.”

Higher education, in particular, will play out completely differently than a lot of people on my timeline have been predicting. If you read my Twitter timeline, you’d come away with an impression that there’s going to be this complete apocalypse of all higher ed institutions; the bubble will finally burst, and the whole system is going to collapse. I really doubt that’s going to happen!

In fact, you can probably make the case that in the long run, the coronavirus pandemic might help sustain the current paradigm of higher education, rather than destroy it. All it takes is one year of seriously threatening to take away everything that makes college great for us to be reminded why it’s so hard to opt out. Yes, some schools will go under. Perhaps many of them. But colleges going bankrupt does not really diminish the value of a college education in terms of it being a positionally scarce resource. If anything it increases it, by sending newly freed students scrambling to find alternate spots at surviving universities.

Oh and also, if the economy isn’t great for the next couple years, you bet you won’t hear too many people saying, “Oh, don’t worry, college is optional in the new economy,”. Nope! That was something we got to pretend to say when times were great (and you already had a college education, or enough privilege that it didn’t matter. Being able to performatively opt out of a positional scarcity ritual like college really just means you already had a ton of it anyway. It’s like Jeff Bezos saying, “you know, you don’t actually have to fly there. Just call them, they’ll still clear their schedule!” Jeff, they’ll clear their schedule for you. You’re already at the front of the line anyway. The rest of us have got to cram into an airplane seat.

So, rest assured: just because coronavirus is putting a temporary pause on some of these positional scarcity mechanisms doesn’t mean we’ll all collectively cast off that weight weight forever. Unless! And this is a big unless – we come up with new positional scarcity gates and barriers during this next year that are just as effective. This is paradoxical (and ironic), but I think it’s true: the way we’ll finally get rid of business travel isn’t by coming up with something that’s cheaper and just as good; it’s by coming up with something that equally expensive, or contains equal friction, in the meantime while we’re waiting.

If we don’t, then we’re just gonna go right back to flying as a way to signal we’re serious about something. And expensive, in-person college campuses and undergraduate degrees will still do the same job of charging for a good spot in line. It’s basic human nature to pursue positional scarcity, and to do whatever it takes to compete for it. The virus won’t change that.

Now, it’s entirely possible that when life resumes, there will be real restrictions and tangible obstacles to travel and other aspects of life we used to take for granted. Business travel may simply be impossible to resume as before. But to any extent we’re able to, we’ll probably go right back to using as a positional scarcity tool – Zoom or no Zoom.

Like this post? Get it in your inbox every week with Two Truths and a Take, my weekly newsletter enjoyed by thousands.

Recent Comments