The Michael Scott Theory of Social Class

I’m happy to finally share a thesis I’ve been chewing on for a little while. I call it The Michael Scott Theory of Social Class, which states: The higher you ascend the ladder of the Educated Gentry class, the more you become Michael Scott.

We should start with one background assumption, which is I’m going to assume you’ve watched The Office (The American version) or at least have a passing knowledge of the main characters. If not, then this idea will probably not land as hard, but I hope you read it anyway.

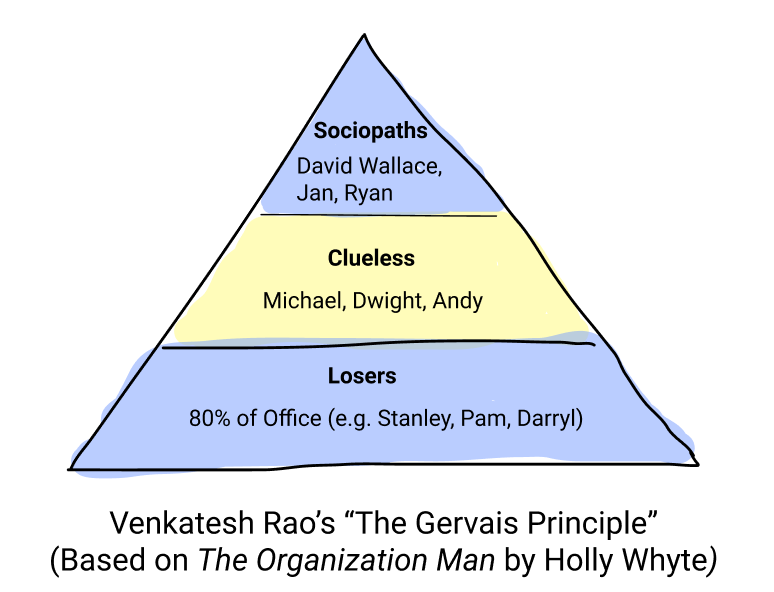

So, twelve years ago, Venkatesh Rao wrote a lengthy and fascinating series of essays called “The Gervais Principle”, which walked through the NBC show The Office, an American adaptation to Ricky Gervais’ original British series. The essays go after a particular aspect of organizational behaviour, around how organizations that survive tend to self-stratify into three predictable layers. (To a large extent, his analysis derives from another magnificent book, The Organization Man by Holly Whyte.)

In the bottom layer, you have around 80% of the office, who occupy the rank-and-file roles. They are the losers. Rao carefully notes that “losers” does not mean uncool, or unworthy; he specifically means “economic losers.” Losers are the people who are set in roles or stations in life where the output of their effort is wholly realized by someone else. As they learn throughout their careers, their skill or engagement might lead to incremental career progress, but no real leverage of any kind. Hence, they are “economic losers”, and they know it. They see the world through clear eyes, and cope.

Three classic examples in the show, spanning the broad range of Losers, are Stanley, in sales; Pam, the receptionist, and Darryl in the warehouse. Stanley is a grumpy loser; he treats the entire workday as a “run out the clock situation”. Pam is a cheerful loser; she generally tries to make the best of things, although fully aware of her reality. Darryl is a smart loser; he’s wise to how the world works, and successfully rules over his little kingdom of the warehouse, but generally understands he’s staying where he is.

Meanwhile, at the top you have Corporate. These are the sociopaths; the economic winners. They are smart, they care about getting power, and little else. The sociopath characters in The Office include: David Wallace, the CFO; Jan (before her series of breakdowns); Ryan the temp, who brilliantly grabs real power only to immediately squander it. And finally, the one character who never quite goes over to the dark side but certainly thinks about it (the real will-he-or-won’t-he drama of the show) – Jim.

The losers and the sociopaths are actually pretty alike. They are alike in that they both see the world through clear eyes, as it actually is. The losers basically understand how the world works, and how their role fits within it. So do the sociopaths.

But in the middle, in between the losers and the sociopaths, is a very different group. That group is the middle managers: the clueless. In The Office this group is an iconic trio: in ascending order of cluelessness, Andy, Dwight, and of course – Michael.

When it really comes down to it, The Office is a show about these three people. Because the real subject of the Office, explored brilliantly over many seasons, is this three-layer structure. At the top and at the bottom you have rational realists, but what’s actually interesting is the clueless in the middle, and how they interact with everyone below and above them.

Michael’s job both shapes, and selects for, a particular kind of detachment from reality. Middle management is a fascinating construct: your employees have literal jobs and responsibilities, and your bosses have literal jobs and responsibilities, but Michael spends his entire day in a construct of his own creation. Everything about his world is subjective and arbitrary. These are people who, in effect, have slipped into a job, worldview, and self-image that is friendly but deeply alienating.

Once The Office gets really established by Season 3, the central drama of the show takes form, which is the Struggle of the Clueless between Michael, Dwight and Andy. Every other character in the show (except Toby in HR, whose explicit isolation from the rest of the group in both the org chart and the office floor plan is flawlessly executed) is at peace with reality to some degree; but not these three. They are tormented by their detachment from reality. But at the same time, they compete with one another to double down on that detachment. (See the ongoing gag around Dwight’s “Assistant To the Regional Manager” title; Andy’s combination of tone-deaf keenness and anger management issues; Michael’s entire existence.)

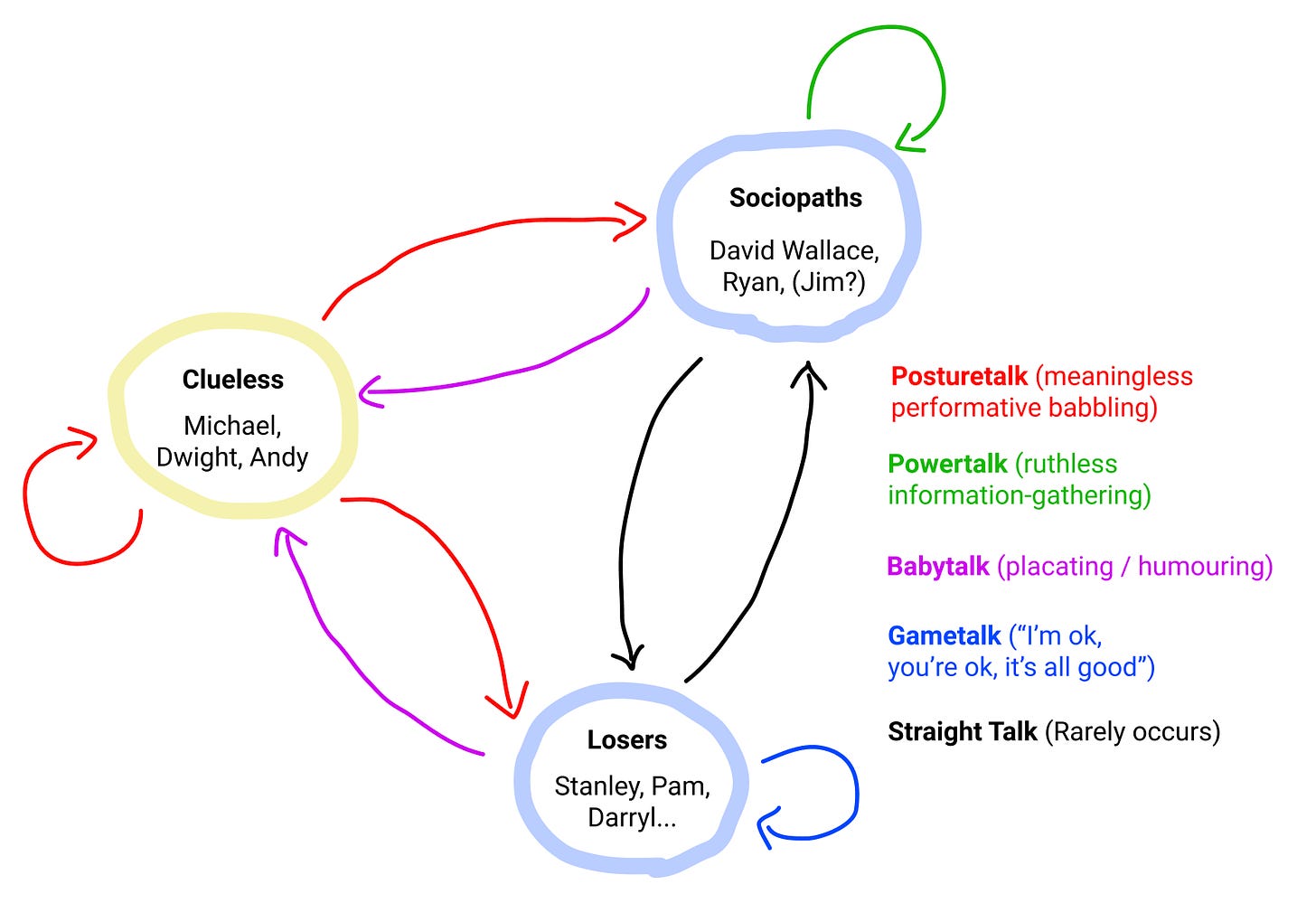

There are many fascinating parts of Rao’s multi-chapter series. I recommend reading through them all. But the most interesting topic he dives into, by far, is language. If you look at the way everyone talks to each other, you’ll find five distinct ways that the characters speak both within and between the three groups.

The first major speech pattern between the characters is Posturetalk. Posturetalk is everything said by Michael, Dwight and Andy, to anyone: the staff, the execs, or each other. Everything they say is some form or another of meaningless, performative babbling. This is the language of living inside a construct; where your entire world lives within arbitrarily drawn boxes, and you have nothing concrete to attach to. It’s the only language that Michael knows how to speak.

When people speak back to Michael, Dwight and Andy, they use a different language: Babytalk. Babytalk is the language spoken from the literal, to the clueless. It’s placating, soothing, or often misdirection: “There, there. You have no idea what you’re saying. Why don’t I distract you with something over here.”

The three other languages spoken, which don’t involve the Clueless, are Powertalk (the Sociopaths’ internal language, which is entirely about competitive information-gathering and retroactive deniability), Gametalk (The Losers’ internal language: recurring games or coded rituals to get through the day), and the rare instance where Corporate actually speaks directly with the losers: Straight Talk. It’s the one and only time where people actually speak directly, with zero encoding.

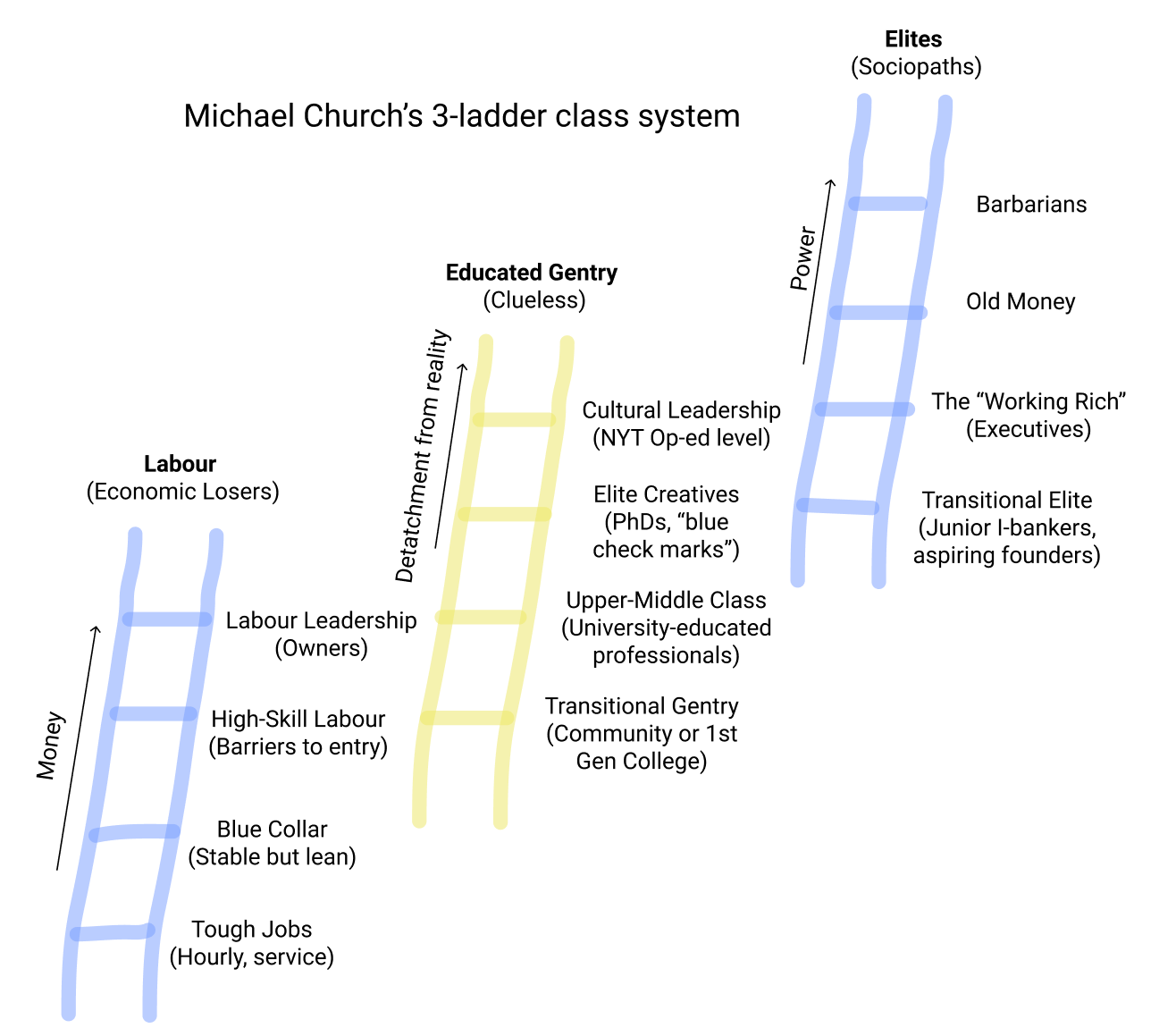

Once you get familiar with this three-tiered realists-clueless-realists structure, you start to see it in other places. One of the biggest stages on which you could argue it plays out pretty faithfully is social class structure in North America.

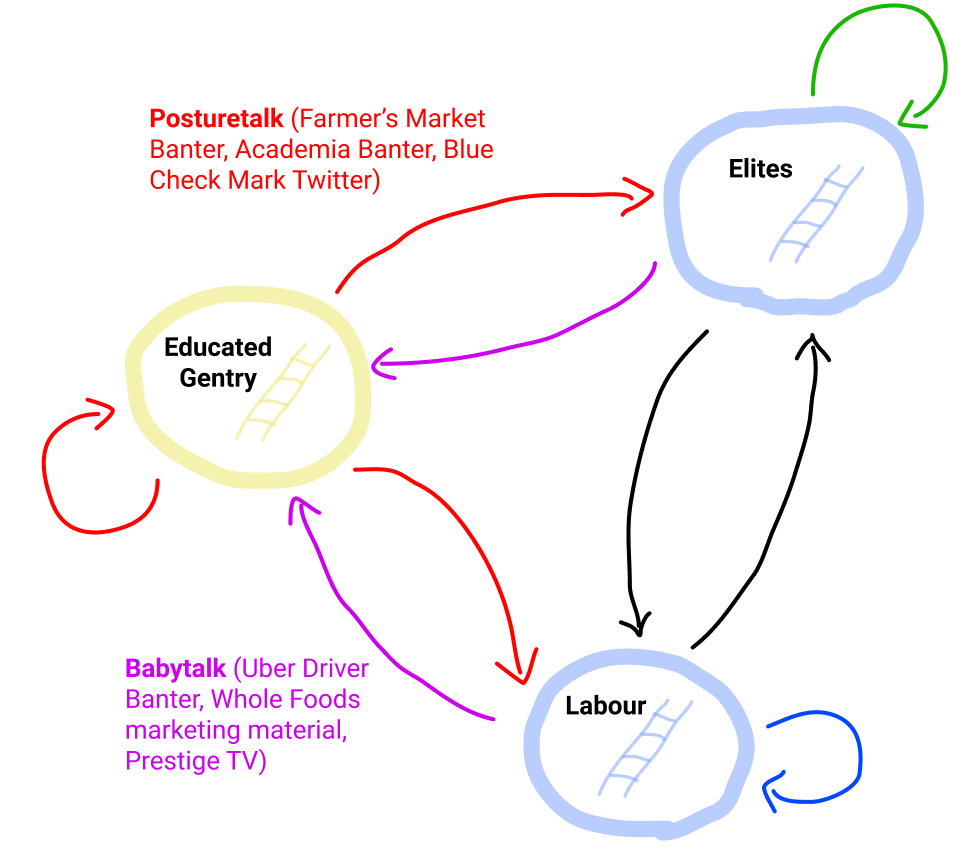

The 3-ladder system of social class in the United States | Michael Church

Several years ago, Michael Church wrote a neat summary of the American social class system, and how the traditional metaphor of “climbing the ladder of social class” is wrong in an important way. There isn’t one single ladder; there are three – each with different values, norms and goals. You have the first, and largest ladder, Labour. Next, you have the “Educated Gentry” ladder that corresponds to what we typically call the Upper Middle Class. And finally, you have the elite ladder. And the remarkable thing about these ladders is how perfectly they correspond to the three-tiered pyramid in The Office, of the losers, clueless, and sociopaths.

Climbing the labour ladder means making more money. At the bottom are really tough jobs, typically paid hourly, informally, or with tips. Above that there are stable, but modest blue collar jobs; then high-skilled or good Union-protected careers. Finally at the top you find “Labour leadership”, which doesn’t mean being a union boss, but means, “You’ve made it. You own stuff. You drive a new F-150, you have income properties, you enjoy nice things.”

If you’ve made it to Labour leadership, you are by no means hurting for money. But you have not actually escaped the category of “economic losers”, because the Labour ladder does not create paths to leverage. That is the fundamental difference between how the labour ladder works versus how the elite ladder works. The people on the labour ladder fully understand this. They see the world as it is, with clear eyes, like Stanley, Pam or Darryl – or the one person who actually makes the jump, Ryan – in The Office.

Skipping the middle ladder for a second, we move to the Elite ladder. The Elite ladder has a lot in common with the Labour ladder: it’s straightforward. You move up by getting more money and more power. The only fundamental difference is that you climb the Labour ladder by working hard, whereas you climb the Elite ladder by acquiring leverage.

The bottom of this ladder is an entry point – junior Investment Banker roles you can jump into, or founding a startup now also qualifies. The next rung up are the executives who run successful businesses. They are powerful, but nervous. Above them is Old Money: the multigenerational dynasties with power that extends beyond business and into media and politics, like the Bushes and extended Vanderbilts. And finally, at the top of this ladder, are the Barbarians. These are the scariest people in the world.

The middle ladder works completely differently from the other two. This ladder isn’t about money or power; it’s about being interesting. You climb this ladder by being more educated, and towards the top, by having costly habits and virtues.

At the bottom is also a transitional layer: it’s how you get onto this ladder if you weren’t born there, often via Community or 1st generation College. Above that is the upper-middle class Petite Bourgeoisie. Higher up the ladder are “elite creatives”, people with obscure or virtuous-sounding PhDs, notably interesting lives, or Blue Check Marks on Twitter. (They may well earn less money than those below them on the ladder – this ladder isn’t about income.) At the very top of this ladder is an exclusive group: “Cultural leadership”. The litmus test for attaining this group is, “could you write an opinion piece in the New York Times.”

Generally speaking, the farther you go up this ladder, the more detached from reality you get. Importantly, this isn’t seen as a problem: it’s actually a virtue, so long as you portray it correctly. Sixty years ago, this group sought refuge and status in the suburbs, explicitly detaching themselves from the reality of dirty, dangerous cities. Now, it’s fashionable to move back downtown, detaching ourselves from the reality of gas-guzzling, chain restaurant normie suburbs. The farther you go into expensive, performative habits (Doing triathlons, eating farm-to-table) and coastal echo chambers (“I don’t know a single person who voted for Trump”; “We should ban cars”), the farther you progress up this ladder.

On the way up the ladder, you earn social status by doing things that detach you from normie reality. David Brooks wrote a fabulous book on this phenomenon called Bobos In Paradise, about the peaceful merger between the Bourgeois and Bohemian classes that created this strange but durable social tier. These are people that would be mortified to show off a $10,000 watch, but excitedly tell you about their $100,000 kitchen remodel filled with 100-mile diet cookbooks and single-origin Japanese knives, or their 6-month work sabbatical they spent powerlifting. This is a group of people where a Subaru is a higher-status car than a Cadillac, but the highest status car is none. (Or, now, a Tesla.)

As with Rao’s piece, there are lots of interesting dynamics that Church gets into here, notably the challenges facing people who try to jump from one ladder to another (with the corresponding code switching and value-recalibration it requires). But what I want to highlight is something Church never covers, but you can see clear as day by superimposing The Gervais Principle on top. And that’s how clearly this three-ladder structure reveals itself through language.

What’s interesting here isn’t the language of Labour or of the Elites – both of these groups see the world more or less as it is. It’s the language spoken by and to the Educated Gentry. Both reveal the extent to which this group has become detached from normal reality, and also the care taken by others (mostly labour) to manage this detachment carefully.

So some examples of Posturetalk (the Educated Gentry talking to anyone; but mostly to each other) include Farmer’s Market Banter (“Praise me for how sustainable I am”), Academia Banter (“Validate my obscure pursuits”) and Blue Check Mark Twitter (“Enshrine my Takes”). Examples of Babytalk (speaking to the Educated Gentry) include Uber Driver Banter (“I’m willing to entertain this conversation but please give me a 5-star rating, I really need it”), Whole Foods Marketing material (“You areso wise for shopping here.”), and Prestige TV (“You are so smart for watching The Good Place”).

The great irony of the Educated Gentry is that the more time you spend in it, and the more people talk to you with that language, the more you turn into Michael Scott. It’s a funny juxtaposition, because Michael Scott in the show is absolutely not in this economic class (he never went to college; his job falls solidly in the labour ladder), but his character is a bang-on portrayal of what’s like to aspire to Petite Bourgeoisie values.

Brock is 100% correct; it is a certainty that Michael Scott knows how to use chopsticks. He’d be proud of it. You could script an entire scene of The Office around the topic of Michael and chopsticks, filled with Michael’s posturetalk (his fully inaccurate beliefs around the culinary evolution of chopsticks, which he recites enthusiastically) and Babytalk from both his coworkers and his server (“Oh is that right? We don’t always get customers who are so knowledgeable. How about I get you another Nog-a Sake?”)

This keeps getting back to why the language part is so important. Michael’s pride in his chopsticks proficiency isn’t a superfluous detail, it’s a consequence of being spoken to in Posturetalk / Babytalk throughout your adult life. When you’re in that environment all day, this is a natural reaction: it’s a kid’s idea of what grownups celebrate. Look at any of Michael, Dwight and Andy’s interactions that highlight proficiencies they’re proud of: Michael’s made up but authoritative-sounding trivia, Dwight’s law enforcement and survival skill LARPing, Andy’s a cappella; these are all upper-middle class values that are stoked by the perpetual fear that your peers don’t take you seriously. (As Brooks points out in Bobos, the highest possible compliment within this social class is to call someone “Serious”, as in, “He’s a serious kiteboarder” or “She’s serious about cooking healthy meals.”)

Language is the fundamental reinforcement mechanism of why arbitrarily constructed environments eventually turn you into Michael Scott. The more you have committed to being seen as interesting within your particular area, the more you detach from reality and move into a construct of your own creation. As this evolution takes place, more of your and your peers’ language will become Posturetalk, and more of the language that gets spoken to you by outsiders will become Babytalk.

As more of the language surrounding you becomes Posturetalk and Babytalk, the more conclusively you will double down on being “serious” about whatever you’re pursuing, as both a defence mechanism and in pursuit of real praise. This drives the cycle forward again, as your values and environment become increasingly defined by doing Triathlons or whatever. Eventually, you become Michael Scott.

To conclude, I present to you the Michael Scott Theory of Social Class, which states that the higher you ascend the Educated Gentry ladder, the more you become Michael Scott. So:

Serious Triathletes? Michael Scott.

PhD Students? Michael Scott.

Have an opinion on the right amount of hops? Michael Scott.

More than 10,000 followers on Twitter? Michael Scott.

Really into urbanism? Michael Scott.

NYT Op-ed? Definitely Michael Scott.

Like this post? Get it in your inbox every week by signing up for my weekly newsletter, enjoyed by 20,000 people every Sunday.

Recent Comments